Faith and Culture. The Future of Christianity. Europe. These are some of the big things I write about here. The challenge is that these ‘things’ are so big and complex that we cannot treat them like simple yes-or-no questions. So, how do we think about big things?

This is one way of looking at it:

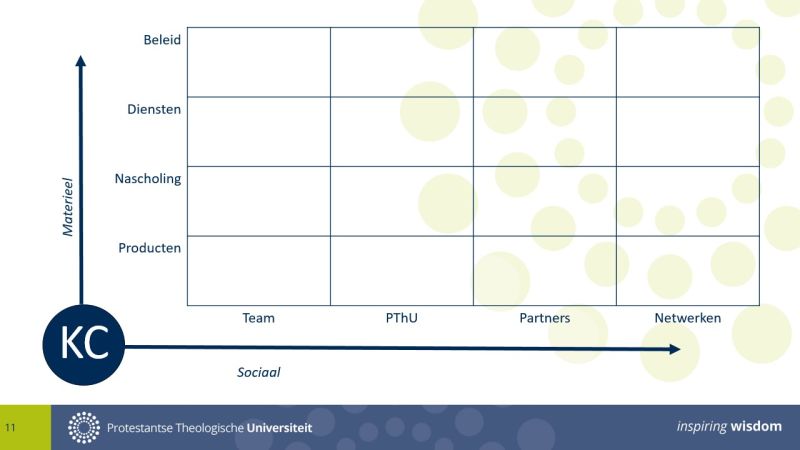

Last month I organised a workshop with my colleagues at the Knowledge Centre for Theology at the Protestant Theological University in Utrecht, NL. In the morning session, we looked at who we are. Inspired in part by John Willshire’s recent reflections on “things” and Zenko Mapping (see here), I presented a social/material matrix for things. No worries if that does not ring a bell, I’ll explain how it works.

The matrix simply maps who we work with (social) against what we produce (material). For example, organising a lecture is both a social activity (working with speakers and audiences) and a material one (producing a tangible event).

A Knowledge Centre is a thing with a social dimension. We are, first of all, a team of four colleagues. As a team, we are tasked with advancing the impact agenda of our (small) university. We therefore work with researchers, lecturers, the board, and various project groups. As a university, we also collaborate with many partners, such as other theological universities, churches, professional bodies, and publishers. Finally, there is a wider network that extends well beyond the university.

As the Knowledge Centre, we are also a thing with a material dimension. We create tangible outputs. These include books, lectures, events, and podcasts. One distinct category is our continuing education offering, with its own structure and workflow. We also provide services. We help colleagues translate their knowledge and expertise into formats that can be shared beyond the university. We advise, brainstorm, and co-create with them. One specific type of service is policy development, usually for the university’s leadership team.

Combining these two dimensions led us to the Social/Material Matrix — a tool for thinking about organisational activities. This helped us see where our energy really goes — and where it doesn’t.

As a team, we used this matrix to map some of our regular activities. After 20 minutes, we had covered most fields with post-its. Of course, there were questions: why are some fields so crowded? Is it okay that we don’t do a lot of X for group Y? Who is most active in which category? The matrix is a good basis for a team heatmap and a starting point for further questions.

Another way to use the matrix is for a life-cycle analysis of projects. This proved helpful in the case of a project in which we first created a publication and then a course. Plotting the transition from one phase of the project to the next made clear where our friction points were. This will help us when planning future projects.

Background

While I was preparing the workshop, my mind went back to a book called “What is a Thing?”. This book is not about ‘objects’, but rather about the question what does it mean for something to be a ‘thing’ at all? The author, Heidegger, argues that a thing is never just a measurable object, but always more than what our modern thinking tells us.

A thing is not just a material resource, a tool or a product. It only becomes meaningful in a world of relationships. For example a book: of course is consists of paper, ink and glue. But is is more then that: it is also knowledge, culture, meaning and a dialogue. The thing ‘gathers’ a world, it ‘reveals’ meaning to us.

A book exists in a web of relationships. This also means that the thing itself changes as its relationships change. A book could be: something for sale in a bookshop, something the reader rembers years later, a useful object in church, an artifact in a museum. The ‘thingness’ changes with the world around it. If we reduce things to measurable objects, they lose meaning, we lose meaning, and the world becomes poorer and flatter.

A philosophical question to ask about things is how they appear as meaningful to us. This question makes sense intuitively, even if answering it is not easy at all. The flipside of this idea is that things are also like a mirror to us. The way we treat things reveals something about how we relate to the world. For example:

- Do we treat the natural world as a resource to extract value from? It shows.

- Do we treat a Church as the place where we meet God? Our behaviour shows it.

- Do we look at ‘the future’ because we are anxious about the present, or disconnected from our past? It will be visible in the way we think and talk about the future.

With that last example, we have made the connection with the ‘things’ we think about here. How can we think about faith and the future of Europe as meaningful ‘things’? What would be relevant questions to explore? (Regardless of whether we draw a matrix for it or not.) I don’t know, but I am interested in hearing your thoughts.